My reflections on the fifth Parliament

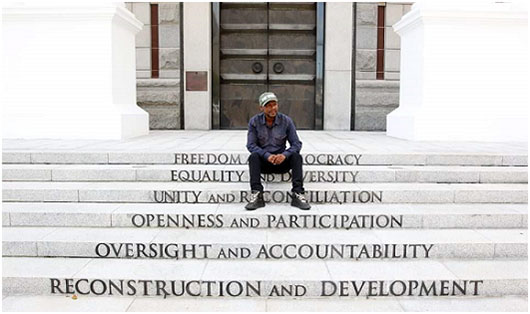

A departing offering of the fifth Parliament, unveiled on the day that the National Assembly rose for the last time, is a series of principles appended to the steps that lead to the building in which the National Assembly holds its plenary sessions.

This has been the site of unprecedented violent inter-party dissent, experienced for the first time in the democratic parliament. It was the fifth Parliament that called members of the South African Police Service into the Chamber for the first time ever, even though this is not permitted.

The fifth Parliament saw the emergence of the controversial “White Shirts”. These were an altogether bigger and brawnier team of mostly former SAPS members, and their job was to provide support when needed to the old parliamentary security services.

They acquired the ironic name White Shirts because they were required to dress formally, this being Parliament, and their muscles and bulging torsos were contained in dressy white shirts which looked entirely out of place when these men physically manhandled and removed dissenting members who refused to follow the orders of the Speaker. There is something destabilising in watching men who look thoroughly respectable but behave like common thugs.

The White Shirts were themselves a source of conflict and tension in the House, being better paid and working fewer hours than Parliament’s own long-standing security service. They were somehow reminiscent (especially to older South Africans) of the brute force and fear associated with the South African police force of earlier and uglier times.

It was not only the presence of the White Shirts that was somewhat disquieting about the fifth Parliament. It was also the knowledge right from the start that the House was wracked with divisions of all kinds, inter- and intra-party, some of which regularly erupted into violence. House protocol could no longer hold the institution together.

So the additions to the National Assembly steps are most welcome. An identical series have also been appended to the steps of Parliament’s other chamber, the National Council of Provinces, and it is hoped that they are read, often, and make an impact on members of the sixth democratic Parliament as they enter to take their seats.

On the first step we encounter the phrase “reconstruction and development”, which is especially welcome as it resonates with the reconstruction and development ethos of our first democratic parliament, and it is mightily encouraging to see the words firmly affixed onto the stone; it’s a way of reminding the elected representatives that the pursuit of reconstruction and development, of all South Africans but mainly the poorest of the poor, is what they are there to do.

Photo: Parliament of RSA

Photo: Parliament of RSAThe next step declares “oversight and accountability”, values that our democratic Parliament is constitutionally required to enforce. One step further up reads “openness and participation”, which reminds all who mount these steps that this was dubbed the People’s Parliament for a reason, and citizen participation and access are founding principles of our democratic parliament.

Another step reads “unity and reconciliation”; the next, “equality and diversity”; and the uppermost step declares “freedom and democracy”.

So, permanently in place are the fundamental constitutional principles that serve as a reminder of everything the institution rests on. Now it is up to those who regularly climb those stairs to perform accordingly, and it is up to us, the citizens of South Africa, to demand that they do so.

There is something ironic and also rather sad about these fine principles being offered by the fifth Parliament as its legacy when it had so often disregarded them. These were painful years when Parliament closely reflected the strife and conflict within the ruling party and between it and the generations of South African who have revered the ANC, sworn allegiance to it, and given everything they had to defend it – including, sometimes, their lives.

Parliamentarians of the sixth Parliament, the people of South Africa ask you to remember these words and read them, daily if necessary, or each time you enter the Houses to serve the people who elected you.

Even when the pace becomes hectic and you are running late, the doors to the Chamber are about to be closed and you are forced to take a short cut and run up the side steps, don’t forget the words underpinning the task you are there to do.

They are immovable and affixed to those steps. If you do need further reminding of what they represent, the bust of South Africa’s first democratically elected president, Nelson Mandela, stands firmly in place just ahead of those steps to the National Assembly, an unmoving sentry to the Parliament over which he first presided.

Please don’t fail him, and South Africa, as the fifth Parliament did, and those parliaments before it that reach back into the Zuma years and even earlier, to the third or maybe it was the fourth Parliament when Members began to forget about the people who had elected them, and their constitutional duty to provide effective oversight of service delivery and their oath to protect and enforce the new rights provided by the Constitution.

Plenaries of South Africa’s fifth Parliament were regularly disrupted by “points of order”. Senior legal support staff spent more time poring over the rule book than the Constitution. The presiding Speaker was most frequently heard calling for “order”, and when that failed, for the Sergeant at Arms, a formidable woman with a calm but impenetrable air of authority. To the surprise of those who have had dealings with her, she would simply be ignored.

The result was Parliament fell far behind in its law-making duties. As time ran out there was a last-minute effort to rush as many Bills through as possible and it was impressive to see how Parliament could function under pressure. However, time is required for committees to probe legislation clause by clause, and to call members of the executive to account for non-delivery. Sufficient public consultation is required by the Constitution, and Bills have been returned on the grounds that they need more comment from the people. Too often there has been a delay while the bells were rung again to rustle up enough Members to constitute a quorate House.

Those Bills that could not be rushed through by the time the fifth Parliament rose may well be reintroduced by the sixth Parliament. These include deeply controversial bills such as the Traditional Courts Bill and the Restitution of Land Rights Amendment Bill, both of 2017. These need attention, not only from the law-makers, but from the public as well, before South Africa forgets that much traditional leadership was the product of apartheid and recognised and bolstered by Jacob Zuma. How can any trace of apartheid still linger in our statute books a quarter of a century into democracy?

The sixth Parliament is unlikely to see the oldest remaining bill revived — the troublesome Mineral and Petroleum Resources Development Amendment Bill. It was introduced back in 2013, passed by the Fourth Parliament but referred back to the Fifth Parliament by the President for re-consideration. The Bill initially stalled in the National Assembly but eventually clearly that hurdle. The Bill was also hamstrung during the NCOP phase and even though the Minister wanted to formally withdraw the Bill, the rules prevent this once a Bill has gone through the National Assembly. So it was left to lapse and die. A new Amendment Bill will probably be introduced instead.

Parliament faced 65 bills to complete before the end of March 2019 — 56 carried over from 2018 and nine introduced in 2019. When Parliament rose, 39 bills were incomplete. These will lapse but can be revived.

This is what the sixth Parliament will inherit, along with the enormous responsibility of voting to amend section 25 of the Constitution, which is based on the Freedom Charter that 64 years ago promised “South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black and white” and made it clear that “the land shall be shared among those who work it”.

We have come to the end of a challenging term, by the end of which South Africans had slowly, disbelievingly, dishearteningly learned about the extent of corruption and the plunder of the fiscus in which so much was stolen from so many.

The sixth Parliament inherits the task of overseeing the recovery of what can still be recovered, cleaning up decades of rot, performing oversight and demanding accountable governance. Even more challenging is its task of restoring public trust in the elected leadership.

It is a big ask, and it will be some time before we know if it will be the Parliament that finally brings South Africa to its knees or the one that proves itself able to pull the country back onto its feet, to stand tall and proudly declare ‘never again’.

Share this page:Share this page:

Review of the 5th Parliament

Articles

- How does the PR system affect the quality of input in Parliament?

- Observing Parliament: my reflections

- A Constitutional Fiction: Parliamentary Oversight of the Executive

- Some thoughts on the Fifth Parliament

- Do small parties work for Parliament?

- View from the opposition benches

- Improving Parliament's ineffective oversight

- Parliamentary Advocacy: How to have an influence?

- Public Engagement: A Case Study

- Notes from the House

- Committee System: performance and areas of reform

- A step forward

- Why has Parliament not yet amended the Budget?

- Points of order (by an observer)

- Diary of a Parliamentary Nerd